Lessons from Fast’s Implosion

How not to scale a startup

I don't know what's going on, and I'm probably not smart enough to understand if somebody was to explain it to me. All I know is we're being tested somehow, by somebody or something a whole lot smarter than us, and all I can do is be friendly and keep calm and try and have a nice time till it's over.

-Kurt Vonnegut, The Sirens of Titan

Some history

Before my startup I had a rather fulfilling career at some of the biggest financial institutions in the world (AIG, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, and Goldman Sachs). I worked at the intersection of data science, machine learning, engineering, and finance on products that helped people. I also got to travel across the world, go to nice dinners, present at conferences, work with exceptionally talented people, and learn from some of the best senior executives in finance.

For someone with my background, this was a dream. Empirically, not many people from the Southside of Chicago get the luxury to work at fancy offices in New York City, and I never took that fact for granted…but I walked away from it to launch my own startup anyway.

As my startup failed, I learned what actually mattered to me in my work and what I missed about my pre-founder life.

In particular,

having and serving customers,

being able to solve problems that mattered,

working with a team on a common problem.

In short, working at an unsuccessful startup was brutally isolating. Everything I missed about my prior life revolved around collaboration with others, maybe with different contexts but basically I missed working with other intelligent humans.

After my soul had taken enough of a beating, I chose to walk away from my startup and go back to working as a non-founder at a fintech, which led me to Fast (my former employer1 and once hot startup).

I found Fast through fintech Twitter and was a fan for a few months before I joined. I don’t remember when but I remember seeing a tweet from Fast’s founder and I became genuinely excited—I even wrote about it.

After the Series B announcement, I decided I wanted to work there. Coincidentally, a friend had joined and he referred me at the end of January. I started in March.

That’s right, I took a job because I liked the company on Twitter. Now if that’s not silly, I don’t know what is…And I’d do it again because life’s too short not to be a little chaotic.

Fast was the biggest risk I had taken in my career—even when I did my own startup I had a full-time job. I worked at financial institutions for so long because I was pretty risk averse, so joining Fast at a high valuation (where there was less upside) was irrational but I figured we at least had the runway for us not to explode in 12 months (ha!).

After the misery of my startup, Fast was exactly what I was looking for and more! Collaboration with extremely talented engineers, a real problem, and customers! I had a blast. It was like drinking a cold glass of water after a year on a desert island. I felt satiated and fulfilled again.

And I urge you to please notice when you are happy, and exclaim or murmur or think at some point, 'If this isn't nice, I don't know what is.’

― Kurt Vonnegut, A Man Without a Country

But this post isn’t about how fun and happy that year was, it’s about how we failed and I’m proud to say that I stood by until the very end. I could have left after some early signs of stress but I didn’t want to.

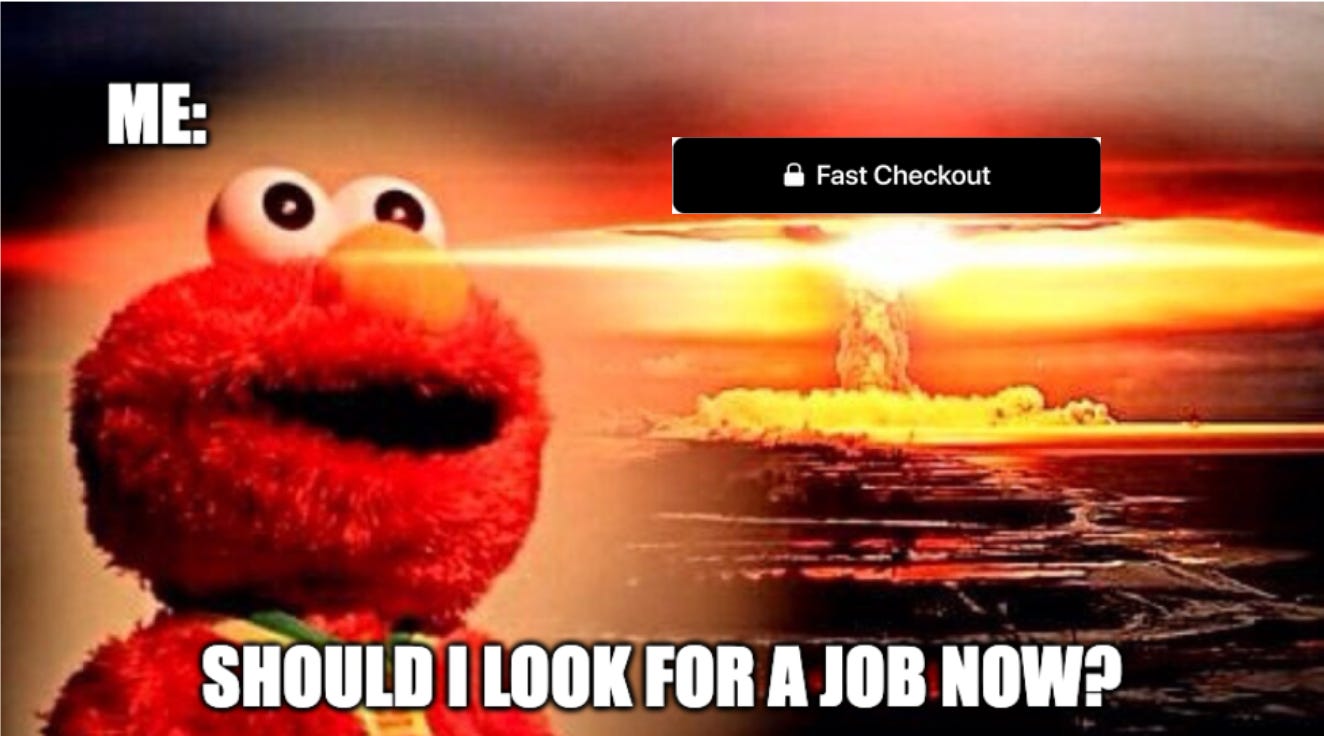

Instead, I went down with the ship watching Fast’s fiery, marvelous implosion.

Note: This is likely the last deep dive I'll do about Fast, as it's not the only thing I want my readers to expect from me but I did want to cover what we did well and what went wrong.

All of the ways that Fast failed

I wrote before about the implosion of Fast and what we did well but I wanted to provide an insider’s view on some of the things I think led us to failure.

Some important facts about my experience at Fast:

I joined just after the Series B announcement

I was there for 14 months

I was approximately engineer #30 (out of eventually ~120)

I also want to be explicit that I don’t blame any individual person for Fast’s failures.

I believe it was a collective failure, in many ways driven by groupthink, and I reject the naive conclusion that there is a single scapegoat or even that a few people are to blame.

We were a team. We failed as a team.

I take pride in having been a part of that team at our peak and at our extremely public explosion.

With all of that context, here’s the list of ways Fast failed:

1. We over-raised

Fast was among some of the startups that raised a megaround at an early stage (i.e., a lot of capital setting the value of the startup extremely high). This has significant consequences because your next round will be harder to grow into. You’ll need to show that you have the numbers to back up the valuation and we didn’t. The biggest numbers we had were from our employee growth from 20 -> 450 in 2 years.

2. We over-hired

This has been discussed at length but it is true, we hired too many people given how our business was growing.

Having too many people caused other challenges along the way, particularly on time spent interviewing and getting people ramped up, but we were still able to ship at a high velocity.

3. We lacked focus

While we did build an impressive tech stack in a short amount of time, we probably shouldn’t have. We should have focused on our core checkout product rather than add all of the bells and whistles that we did2. Our core product didn’t have product market fit yet and we should have focused our effort there before adding everything else we did.

4. Our product was confusing

We had data that some of the specific implementation details of our checkout confused shoppers. Since we didn’t focus enough on improving our core product, we didn’t address this like we should have, and it was a legitimate problem. Having a confusing initial product isn’t necessarily a huge problem in general so long as you iterate and continue to improve the flawed points of your product, but we didn’t.

5. We had too much churn3

We actually didn’t have a big problem getting merchants on our platform. We had a retention problem, again driven by intricacies with our product that caused merchants to leave. In the early Fast days we focused on small to medium sized businesses and they ended up resulting in too little revenue and were unforgiving for any mistakes that took their checkout down (rightly so). We also ended up wasting time on building product features for them when it probably didn’t make sense to.

6. We made bad bets on enterprise deals

We often built features for enterprise customers in hopes to close them but then many would not work out for whatever reason (this is par for the course in enterprise deals by the way). These were high risk bets and we lost. That is kind of the nature of enterprise relationships, and most advise not to be reliant on them for early stage startups. I agree.

Between the struggle to close enterprise deals and merchant churn, we had a significant problem: we were either chasing new revenue or losing existing. For a checkout product, you need significant transaction volume for the economics to make sense and the best way to generate that is through a big company that already has it. Going through many small merchants to increase our customer network simply didn’t work fast enough for us. Any new checkout product will have to solve for closing one big customer and having the tech stack to support them from day one—if we would have stretched our runway maybe we could have4.

7. We had a culture of too much hype and unrealistic positivity

Overall the culture was insanely fun and positive, which was great! But, given my experiences at Goldman, there is a healthy level of skepticism, calculatedness, and calmness that everyone should have. I’m not saying be a robot or all doom and gloom (in general I think excitement is great because life’s too short to be negative) but it’s important to be pragmatic and fight for your startup’s survival. We simply didn’t.

Because of the significant amount of capital we raised there was some complacency (i.e., some thought we already were successful) and I think we could have pushed harder in some areas.

You should assume your startup is dead until proven otherwise and even after a liquidity event it is best to fight for your survival anyways—especially in this economic environment.

8. We mistook dogma for vision and conviction

In my own startup I thought I was placing high conviction bets and later realized I was just ignoring reality. I saw this often at Fast as well. We hired strong leaders with strong opinions, but ultimately strong opinions that do not bend to data are probably doomed.

Some call this behavior being relentless, having strong conviction, or even being a visionary but, in reality, the average case likely doesn’t play out well with this approach and it’s probably more effective to be both balanced and responsive to the feedback you get.

9. We ignored warning signs

We tracked metrics, but metrics alone weren’t enough. We should have taken stronger action to course correct.

We monitored our transaction volume everyday, so we knew that our revenue wasn't what it needed to be. From a company and investor’s perspective, we should have reshuffled our priorities and down-sized5 the company.

We also paid close attention to our merchant numbers too and, as mentioned, we had too much churn. Then we pivoted to enterprise customers but they churned too. We ignored our merchant churn and I think it was a reflection of the weak points of our product. We should have focused on our core product until our churn was much lower and then gone to enterprise.

How to avoid some massive failures

Don’t do the things I listed above. 😉

More seriously, I think our biggest failures were being too irrational, dismissive of some unpleasant truths, and not course correcting fast enough6…but part of startups is being irrational and taking high stakes gambles. We just happened to be on the losing end this time.

So, really pay attention to your feedback, it is a gift. It’s great to have a north star but surviving is much more important.

Closing Thoughts

My time at Fast was amazing, especially after the isolating misery of my own startup.

I don’t regret a single thing and I would do it all over again even if the outcome was the same because of the relationships I made, fun I had, and lessons I learned.

More importantly, my startup failure and the failure of Fast led me to Affirm, a company I was already extremely fond of because of the mission, founder, values, and product. In fact, if you look at my background, I really couldn’t have picked a better company to end up at. Affirm works at the intersection of all of the things I am deeply passionate about: e-commerce, finance, technology, the internet, machine learning, and, most importantly, has a mission to help people—the very thing that brought me into fintech. Glorious serendipity.

A wise old friend of mine used to say, “The past couldn’t have happened any other way.”

It’s true and I’m grateful that my failures led me to where I am today.

Happy failing. 🚀📈📉🧨🪦

-Francisco

Postscript

Did you like this post? Do you have any feedback? Do you have some topics you’d like me to write about? Do you have any ideas how I could make this better? I’d love your feedback!

Feel free to respond to this email or reach out to me on Twitter!

A very fortunate outcome was that I get to continue my fast shipping endeavors with the majority of Fast’s engineers at Affirm, which is an incredible place to call home. 🤗

This probably includes even hiring me to build many of the features my teams built. So this is from the lens of investors and business owners.

As it turns out the Burger King guy was right about the long-tail of e-commerce platform integration complexity.

Though this isn’t necessarily true as many of the features that people liked about our product were developed by the new and talented engineers we brought so it’s kind of disingenuous to truly believe this.

Probably me included. rip. 🪦

Yeah, yeah the irony is clear.

"strong opinions that do not bend to data are probably doomed."

great point

So nice to read a honest take on a failed startup! This side of story is often skipped and we end up focussing on success stories only!